| Money is what you can get away with. Money is confidence.

Money is the trust that others imbue in magical pieces of paper.

Scam artists and central bankers know this. Just look at the

shares of Bre-X Minerals. Look at the U.S. dollar and the

Russian ruble. You print the paper, and they give you the goods.

Magic.

Reality is also what you can get away with. Joshua Norton I,

first Emperor of the United States, taught us this lesson.

That's why we love him. He was a sovereign individual who

learned to live free in an unfree world.

Joshua Norton was born in England in 1819. He migrated to

South Africa with his parents, and spent his childhood there.

Not much is known about this period. He then arrived in San

Francisco in 1849, about 30 years of age. That was the time of

the California gold rush. But Norton already had money in his

pockets--in the neighbourhood of $40,000.

While others panned for gold, Norton set himself up with in

the import business, and in real estate, and built a respectable

fortune. It is said to have grown to about a quarter of a

million dollars by 1853.

Then he tried to corner the rice market. He foresaw a large

demand for rice from the many Asiatic workers in the City of San

Francisco. So he bought up as much rice as he could afford. And

the price of rice soared. But Norton held on to his rice hoard

too long. Two ships filled with rice arrived in port. With the

rice supply thus vastly increased, Norton's own rice holdings

became virtually worthless.

Norton went bankrupt and disappeared for a while. Then in

1857 he came out of hiding. He formulated a new plan. On

September 17, 1859, he placed a notice in the San Francisco

Bulletin declaring himself Norton I, Emperor of the United

States. He later added Protector of Mexico to his title.

He also ordered representatives of the various states to meet

in San Francisco's Musical Hall the following February "to make

such alterations in the existing laws of the Union as may

ameliorate the evils under which the country is labouring and

thereby cause confidence to exist, both at home and abroad, in

our stability and integrity."

You had to be there to know what actually went on, but

Norton's reign was uncontested by the states. He began to appear

in public in full military dress. He wore a blue uniform with

gilt epaulets and shiny brass buttons. He preferred a beaver

hat, with a rosette, and topped with peacock feathers. To this

he added a cane and umbrella, or else a ceremonial sword, and

his naturally sovereign bearing.

Thus Norton ruled the streets of San Francisco. On his daily

walks throughout the city, he made certain that all sidewalks

were unobstructed, the police were not sleeping on the job, and

buildings under construction obeyed city ordinances.

He ate in fine restaurants as the guest of the owners, who

vied for his patronage and approval as his fame spread.

Transportation was provided free of charge. At one point the

city provided an annual sum for the Emperor's trappings. He sent

telegrams to other world leaders, who sometimes responded.

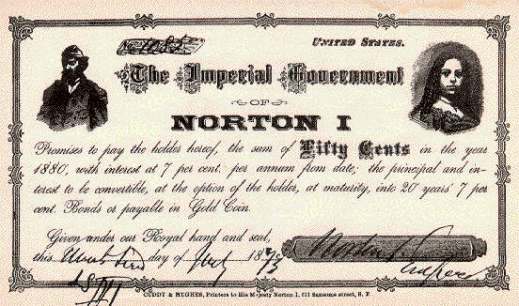

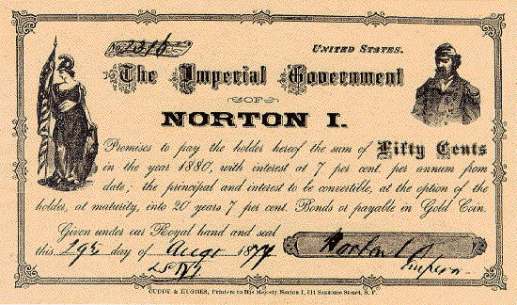

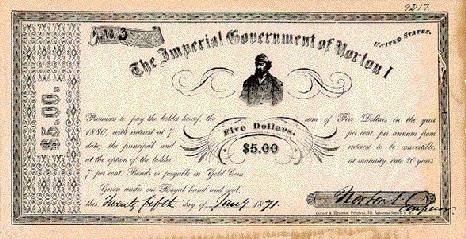

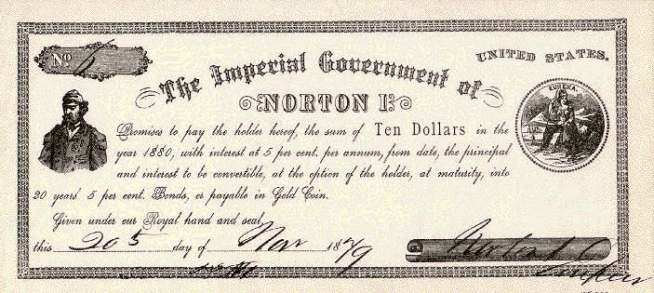

Norton issued his own money.

There were the

50 cent notes of 1873 and

1877, the

five dollar bill of 1871, and the

ten dollar bill of 1879, as displayed here.

The citizens of San Francisco gave the Emperor the tribute he

expected. He was listed in the city directory as "Norton, Joshua

(Emperor), dwl. Metropolitan Hotel." He lived in a lodginghouse

on Commercial street. He refused to rent by the week, but paid a

daily rate for 17 years. He had two dogs, Lazarus and Bummer,

who were with him constantly, even in church on Sunday.

When a new dogcatcher took Lazarus into custody by mistake

once, an angry mob gathered to protest, and city officials

quickly announced that both dogs were to have free run of the

city. When Lazarus died, his funeral was attended by thousands.

Norton ensured that proper respect was paid the City in

return. "Whoever after due and proper warning," he proclaimed,

"shall be heard to utter the abdominal word 'Frisco,' which has

no linguistic or other warrant, shall be deemed guilty of a High

Misdemeanour." Penalty for non-compliance was $25.

In July of 1860 Emperor Norton saw trouble brewing between

the North and the South and declared that the Union was

dissolved for the duration of the emergency. In 1869, he ordered

a bridge built across San Francisco Bay, although it would be

sixty years later before the Oakland-San Francisco Bay Bridge

became a reality.

Perhaps Emperor Norton's greatest proclamation appeared in

the San Francisco Herald on August 4, 1869:

". . . [I] do hereby dissolve and abolish the Democratic

and Republican parties, and also do hereby degree the

disfranchisement and imprisonment, for not more than ten,

nor less than five years, to all persons leading to any

violation of this our imperial decree."

The Emperor called for a world of individuals engaged in

creative work. Waiters and busboys were to present lectures, and

philosophers to clean tables. "I could argue all day about the

significance of facing east in religious rituals," Norton said,

"but a clean table is a clean table."

He drew up plans for mile-high buildings, for great

ocean-going balloons propelled by bicyclists, and for a network

of tubes beneath the city to speed postal deliveries. The

records of his many planned enterprises were lost in the great

fire of 1906.

Norton died suddenly on January 8, 1880, while making his

daily rounds. Area flags were hung at half mast. Businesses were

closed. The funeral arrangements were the most elaborate the

city had ever seen, with 20,000 people paying their last

respects.

Emperor Norton, we salute you.

Bibliography

Cowan, Robert Ernest. Norton I, Emperor of the United

States and Protector of Mexico, San Francisco, California

Historical Society, 1923.

Drury, William. Norton I, Emperor of the United States,

New York, Dodd, Mead, 1986.

Kramer, William M. Emperor Norton of San Francisco : a

look at the life and death and strange burials of the most

famous eccentric of gold rush California, Santa Monica,

Calif., N. B. Stern, 1974.

Lane, Allen Stanley. Emperor Norton, the mad monarch of

America, Caldwell, Id., Caxton Printers, Ltd.1939.

Ryder, David Warren. San Francisco's Emperor Norton : the

story of Norton I, Emperor of America and protector of Mexico,

San Francisco, Alex.Dulfer Printing and Lithographing Co., 1939.

The Adventures of Bummer & Lazarus in old San Francisco, a

true story, San Francisco, Londonborn Publications, 1985.

|